[理工学部、建築・環境学部教養学会ミニ講演会] (第69回理科系学生のための公開英語講演会)

English Lecture Meetings for Science-Major Students

Pavlov’s Dogs

パブロフの犬:条件反射はヒトとイヌだけの行動か?

講師:理工学部、数理・物理コース

北村 美一郎 先生

On October 14th, 2024, the 69th session of the English Lecture Meeting for Science Major Students was held under the sponsorship of the Academic Society of Faculty of Liberal Arts, inviting Dr. Yoshiichiro Kitamura in the College of Science and Technology to give a lecture with the above title, which was the 9th opportunity on which the lecturer gave a talk to the audience consisting mainly of science major students.

In the introduction of this lecture, Dr. Kitamura showed that animals are capable of associating two independent pieces of information from the outer world. As we know, in the case of Pavlov’s experiments, his canine subjects changed their behaviors after having associated in their minds the sound of a bell with presentation of food.

Interestingly, associative learning occurs as a process of learning for a lot of other animals in various manners, and the pieces of information to be associated in the process can also differ in each case. As an example of such extensive cases of associative learning, Dr. Kitamura mentioned the fact that mice can retain their memory about the space surrounding themselves, the result of the experiments that suggest that rodents (げっ歯類) can associate in their minds the information about their environment and its spatial orientation.

Dr. Kitamura explained: “So, I would like to introduce a method for measurement of another type of memory quoting the result of experiments using rodents as subjects. Rodents include animals like mice, rats, capybaras and so on. Another memory in question here is “spatial memory.” Spatial memory is a kind of memory for recording information about one’s environment and its spatial orientation. As an example, if you were now in Kanazawa-hakkei station, and someone asked you the way to our university, you could explain where our campus is, because you know its location. That represents a very simple case of spatial memory. When scientists make investigations into spatial memory, they often use animals like mice. The problem, however, is that, as you know, mice cannot speak; therefore, we cannot tell whether they know the way to some destination.”

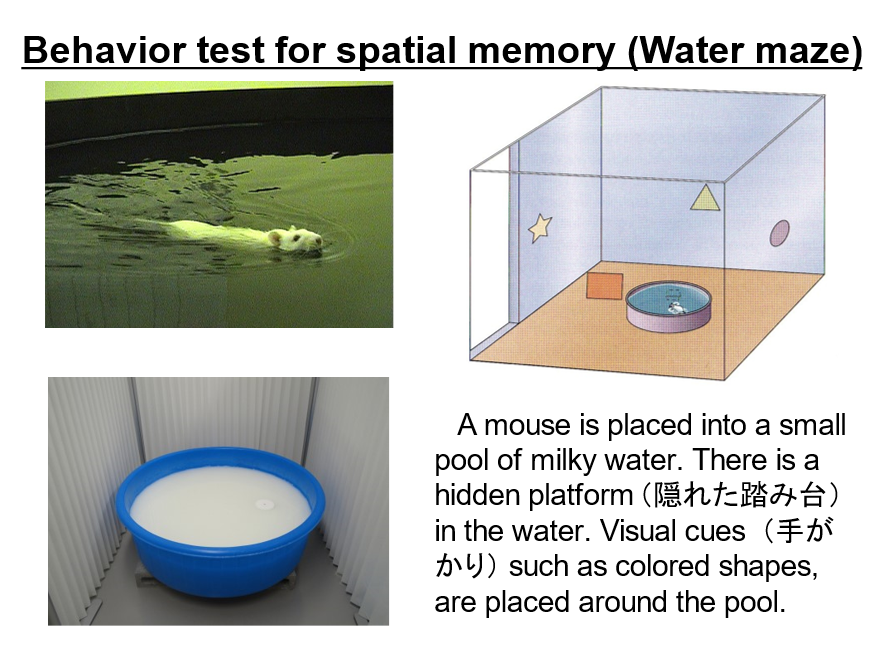

Dr. Kitamura went on to explain: “Now, how can we judge whether these silent animals have spatial memory? This slide illustrates a behavior test for spatial memory, which is called “Water maze.” A mouse is placed into a small pool of milky water. There is a hidden platform in the water, which is invisible to the mouse. Because the mouse hates to get wet or drown, it swims and tries to keep afloat. Hoping to escape from the water, when the mouse has managed to reach the platform one way or another, it can take a rest there. Small plates with different shapes and different colors are placed around the pool as cues for the mouse to locate the invisible platform under the milky water. Just as was expected, the result of the experiments showed that using these cues, mice could locate and memorize the position of the hidden platform.

Significantly, Dr. Kitamura points out that this experiment shows that the rodent subjects have obviously undergone the process of “learning,” as evidenced by the fact that while the mice at first used to swim around randomly trying to find where the platform was, after the training for a while they got to learn where the platform was, and finally, managed to swim straight to the platform.

After having introduced various distinct modes of associative learning that animals show, Dr. Kitamura concluded this lecture with the following remarks: “Please remember the title of today’s talk, which is “What do animal behaviors teach us?” As we now understand, observation of behaviors of animals or even microorganisms can be of great help to understand their emotional or intellectual conditions. We can measure the memory of animals as in the case of Ivan Pavlov’s experiments with dogs, or we can measure the strength of a particular emotion such as “anger” as in the case of experiments with crickets. Thank you for your attention.

After the lecture, six questions, of which the following represents, were raised by the audience. Dr. Kitamura gave detailed answers to all of them:

Q. I would imagine that Ivan Pavlov’s discovery of classical conditioning has had a significant influence on modern psychotherapy and counseling methods. Could you show us how it has done so?

A. As mentioned earlier, experiments of classical conditioning by Ivan Pavlov produced behavioral therapy for metal disease treatment. This is a picture of Dr. Joseph Walpe, a South African psychiatrist who developed a theory of behavioral therapy known as “reciprocal inhibition(逆制止法)” or “systematic desensitization(系統的脱感作法).” If you are interested in psychotherapy or counseling methods, especially how the theory of classical conditioning was applied to the treatment of human diseases, you should study Dr. Wolpe’s work.